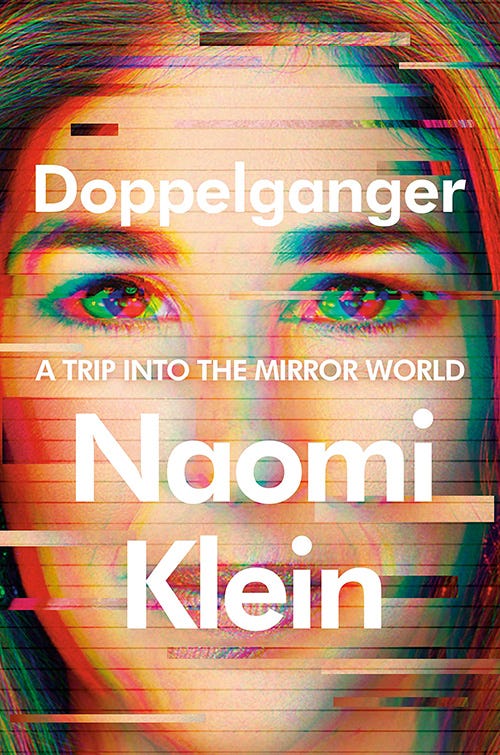

Doppleganger, Naomi Klein (2024)

Doppleganger, Naomi Klein (2024) An easy read that can be devoured in a few days, kind of like an extended Twitter scrolling session - which is also a phenomenon discussed in these pages. A leftist intellectual but not properly an academic (even though she has held academic posts), Klein became famous with the anti-globalization No Logo back in 1999 and built on that with The Shock Doctrine in 2007.

Here she writes about “another Naomi” with whom, especially after the rise of social media, she began to be frequently confused: feminist author Naomi Wolf, who thus takes on the eponymous role of Klein’s online “doppleganger” or alter ego. The (predictable) twist is that unlike Klein, Wolf eventually follows an all-too-familiar path from leftist politics to hard-right views, especially accelerated by COVID and its attendant traumas and dislocation. Originally making her reputation with a book about the burden faced by professional women in adhering to unattainable beauty standards, Wolf by 2021 was writing about the “tyranny” of mask and vaccine mandates, becoming a regular on Tucker Carlson and Steve Bannon’s shows, and ultimately embracing and being embraced by some of the most extreme circles and personages of the MAGA far right.

Klein thus uses her frequent online confusion with Wolf both as a source of humor and a way of analyzing the political discourse, polarization, and chaos of the post-Trump era. She traces Wolf’s ideological journey, not without some sympathy, and analyzes the coalitions and strategies of her new allies - especially Bannon, who she argues convincingly should not be underestimated either as a thinker or strategist. She makes a coherent case that the preoccupations of anti-vaxxers, Q-Anoners, Great Replacement theorists, Proud Boys, Wellness freaks, etc etc, are not simple lunacy, but twisted overreactions to genuine problems, as well as (often simultaneously) cynical exploitations of those same genuine problems. Vaccine skepticism, and distrust of state-mandated public health measures in general, is not unwarranted, especially given the underfunding and neglect of the American public health sector; it’s just rampantly exaggerated and weaponized in bad faith by social media manipulators. Klein also recognizes her own ideas, especially the “shock doctrine,” as being recycled and twisted into funhouse mirror versions of themselves, much as Trump twisted the leftist notion of the “deep state,” a maneuver which does two things: rebuts the original argument the concept was invented for, and also makes the whole discussion feel like unfocused bullshit. And Klein is not unsympathetic to the anti-elitism of the MAGA bashing of the philanthro-liberal Davos elite, but also points out that, in its immoderation and fantasy, it puts her in the odd position of defending, to a degree, that very centrist elite.

No one could call this a disciplined book; Klein goes off on some very long tangents, including about autism, Israel and Jewishness, turn of the century Vienna, and others. She doesn’t so much develop a coherent theory of the “doppleganger” of her own, so much as she haphazardly collects literary, psychological, and mythological references to dopplegangers and throws them all at a figurative wall to see what sticks (most strangely, but also fascinatingly, in a prolonged exegesis on Philip Roth’s Zuckerman trilogy). But honestly, there’s an enjoyable playfulness to this; a more disciplined book (such as a junior academic might write) would probably also be a more boring book and wouldn’t take the reader to some of the interesting places and phrases Klein’s imagination prefers to go. And the ideas are, if this is not setting the bar too low, at least far deeper and more developed than the 140-character Tweets that comprise the political-intellectual muck we are currently stuck in, and which provide the context for the confusion and conflation of the two Naomis and their ideational worlds. (Read mid-June 2024)